A Data-Driven Approaches to Neighborhood Change

This repository stores resources and project data for labs examining data-driven approaches to urban policy and exercises for regression analysis in the public policy context.

Neighborhoods Matter

Hundreds of studies have demonstrated that the odds of economic success vary across neighborhoods. The far more difficult question is whether that’s because neighborhoods nurture success (or failure), or whether they just attract those who would succeed (or fail) anyway.

Urban policy scholars have long made the case for the primacy of place:

- Ellen, I. G., & Turner, M. A. (1997). Does neighborhood matter? Assessing recent evidence. Housing Policy Debate, 8(4), 833-866. { pdf }

Economists have more recently come to the conclusion that neighborhoods matter more than they expected. For example, see

- Justin Wolfers: Why the New Research on Mobility Matters: An Economist’s View; The New York Times, May 4, 2015. { link } { pdf }

- Raj Chetty: The Economist Who Would Fix the American Dream; The Altantic, August 2019. { link } { pdf }

There is growing evidence that neighborhoods can be viewed as an important TREATMENT that aids in social mobility, i.e. holding the household and socio-economic status constant, the same child will achieve very different lifetime earnings if you change the neighborhood in which they grow up. This is the basic premise of place-based policies - if you improve the neighborhood you improve outcomes for families that live in the neighborhoods.

Similarly, programs which help low-income families move to stable and thriving neighborhoods have significant long-term impact on the mobility of the kids.

- See the Moving to Opportunity Study { Part 1 } and { Part 2 }.

The Quality of Neighborhoods Varies Significantly

The report shows how America’s yawning inequality extends beyond just money to wide discrepancies in health, knowledge and education, too. As Stanford economist Rebecca Diamond has suggested, inequality of well-being compounds earnings inequality. Her research finds that more well-off and high-skilled Americans accrue additional benefits from living in neighborhoods with better schools, less crime and enhanced public services. Meanwhile, the less skilled and moneyed Americans are shunted off to communities with low quality schools and services. America’s economic divide registers not just in what we can afford to buy, but in the education we have the opportunity to attain and, most basically, in how much time we have to live.

The Geography of Well-Being, CITYLAB, Richard Florida, APR 23, 2015 { link }

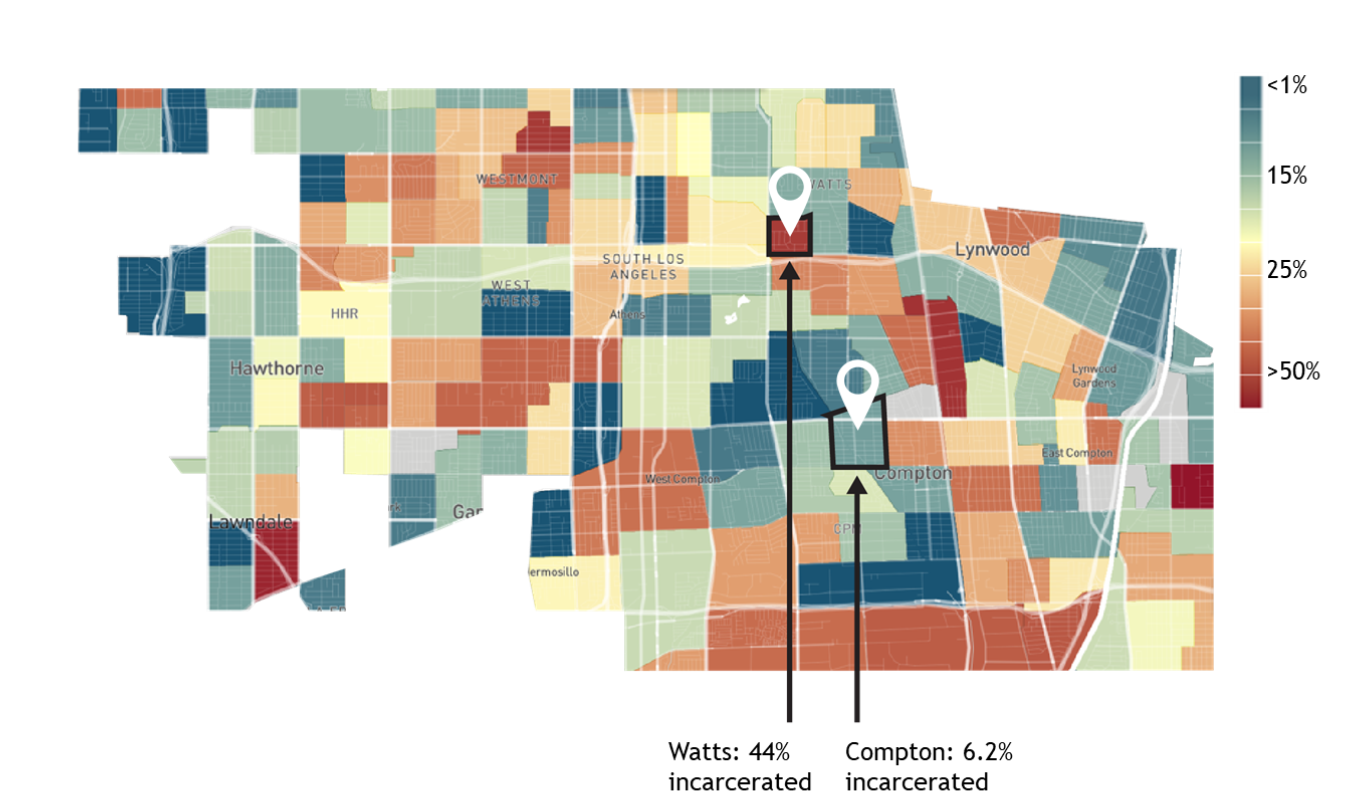

Incarceration Rates for Black Men Raised in the Lowest-Income Families in Los Angeles, by Neighborhood in which they Grew Up cite

Theories of Neighborhood Change

Neighborhoods don’t start out bad. They typically begin as vibrant middle-class developments that pass through various life-cycles over time. Why do some neighborhoods remain stable and thriving, and others experience drastic decline and stagnation? Theories of neighborhod change help answer that question.

- Pitkin, B. (2001). Theories of neighborhood change: Implications for community development policy and practice. UCLA Advanced Policy Institute, 28. { pdf }

Data-Driven Approaches to Studying Neighborhoods

Data can help us better understand the impact that neighborhoods have on residents. This class will help you develop a framework around community analytics - using data science tools to identify and describe neighborhoods in cities, and predict how they might change over time.

We will specifically draw upon approaches described in:

- Firschein, J. (2015). Putting data to work: data-driven approaches to strengthening neighborhoods. IFC Bulletins chapters, 38. Market Value Analysis: A Data-Based Approach to Understanding Urban Housing Markets, pp 41-60. { pdf }

Some data-driven models that help predict which neighborhoods are most likely to change over time.

And recent academic work that uses census data and machine learning to identify patterns in community development:

- Delmelle, E. C. (2017). Differentiating pathways of neighborhood change in 50 US metropolitan areas. Environment and planning A, 49(10), 2402-2424. { pdf }

All three articles share a common approach of using census data and clustering techniques to classify neighborhoods by type, then examine how each type is likely to change over time.

References

- Ismay, C., & Kim, A. Y. (2019). Statistical Inference via Data Science: A ModernDive into R and the Tidyverse. CRC Press.

- St. Clair, T., Cook, T. D., & Hallberg, K. (2014). Examining the internal validity and statistical precision of the comparative interrupted time series design by comparison with a randomized experiment. American Journal of Evaluation, 35(3), 311-327.

- Aiken, L. S., West, S. G., Schwalm, D. E., Carroll, J. L., & Hsiung, S. (1998). Comparison of a randomized and two quasi-experimental designs in a single outcome evaluation: Efficacy of a university-level remedial writing program. Evaluation Review, 22(2), 207-244.

- West, S. G., Biesanz, J. C., & Pitts, S. C. (2000). Causal inference and generalization in field settings: Experimental and quasi-experimental designs.

- Ferraro, P. J., & Miranda, J. J. (2017). Panel data designs and estimators as substitutes for randomized controlled trials in the evaluation of public programs. Journal of the Association of Environmental and Resource Economists, 4(1), 281-317.